|

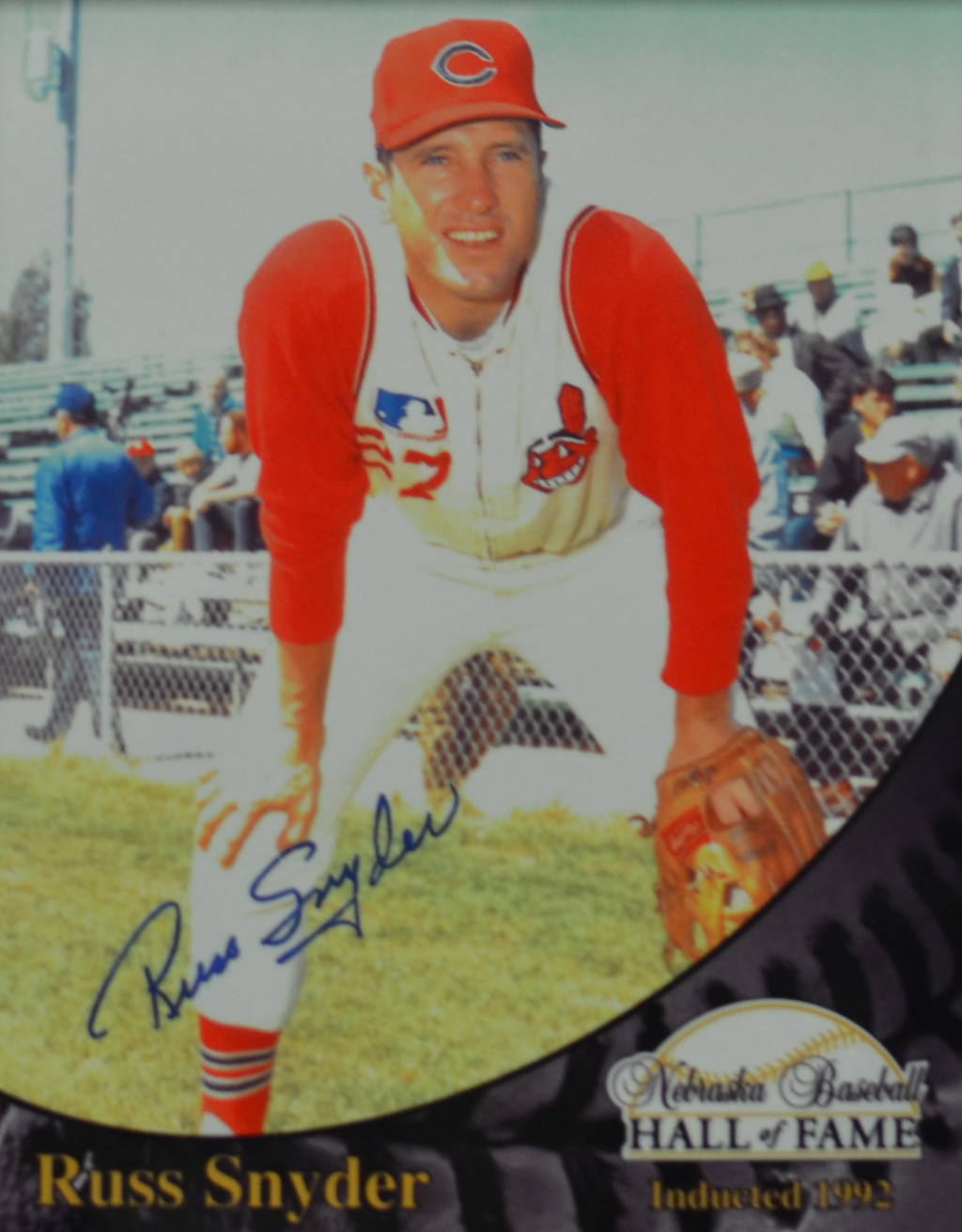

This article was written by Monty Nielsen Russ Snyder TRADING CARD DB Russ Snyder inked his first professional baseball contract with the New York Yankees in August 1952, just three months after graduating from high school. The next summer he was the top hitter in the minors - compared at the plate, on the bases, and in the outfield to Mickey Mantle, possibly a cross-pollination of Ted Williams and Ty Cobb. McAlester Oklahoma News-Capital sports editor Hugh T. German saw superstar potential in Snyder and cast him as 'another Mickey Mantle with a little more experience under his belt.' By comparison, German noted that 'Russ runs like Mantle, handles himself well in the field and should take his place alongside Mickey in a few years.'Some saw him being there sooner, noting that 'a kid named Mickey Mantle did it, and with a blazing bat and speed to match in the lower minors. .. Snyder fills the bill on both counts.'Other Oklahoma sportswriters envisioned that Snyder's 'speed and eagle eye' could hasten him down 'the path made by Mickey Mantle.' But Snyder wasn't a ballplayer of Mantle's magnitude. Physically, like Mickey, he could drag a bunt, sprint, and beat the throw to first—but antithetical to the powerful slugger, he was not a home run hitter. Ultimately, what Snyder became was a versatile platoon player, a reserve outfielder for five teams over 12 major-league seasons 1959-1970. His best years were with the up-and-coming Orioles of the 1960s, and he was an important cog in Baltimore's first World Series championship club in 1966. Russell Henry Snyder was born on June 22, 1934, in Oak, Nebraska, population less than 100, in the south-central part of the state. He was the only child of William F. and Minnie Ruth Hauser Snyder, both of whom worked for the Chicago and Northwestern C & NW Railroad in Oak. William was a section head for 17 years, while Ruth was a caretaker for the train depot.7 In a May 6, 2022, face-to-face interview at his home in Nelson, Nebraska, with the author, Snyder said that Stan Musial, whom he never met or saw play, was his baseball hero growing up. Snyder and baseball fans throughout Nebraska and the Midwest, prior to the great western expansion of major league baseball, and well before routine television coverage, could cheer Musial's St. Louis Cardinals over the local airwaves via the medium of radio, day and night all season long. They simply were winners and occasional champions, who became the 'home team.' He went on to describe how he played baseball with his boyhood buddies from Oak and surrounding communities, early on through Midget and Junior Legion levels for another town, Geneva, 30 miles to the north and east. The boys were under the guidance of Joe Bender. Geneva had several good players, and even beat teams from Omaha in Legion tournaments. Snyder was appreciative of the sacrifices made by his dad and mom at that time. During baseball season, they drove 60 miles round-trip from Oak to Geneva twice a week, taking him to games and practices. They watched all his games. If he played well, they were supportive, and if he didn't, they still were supportive. Snyder was a right-handed pitcher and first baseman who always hit from the left side. In 1951, during a Legion tournament game at Duncan Field in Hastings, Nebraska, the 17-year-old Snyder 'slammed a 448-foot homer to the foot of the flagpole.'That fall, he returned to the gridiron as a back for Nelson High School. At 6-feet-1, 165 pounds 190 as a big-leaguer, he was a first-team selection for the Hastings Daily Tribune's All Big 8 Conference Team. Following basketball season, Snyder ran track and field. He also played the piano and sang in the choir. He graduated with the Class of 1952. That summer he narrowed his focus to playing baseball. Snyder had been scouted as a high school player by Floyd Stickney, player-manager of the Superior Knights semipro team in the Nebraska Independent League NIL. Stickney signed him for the summer of '52 season. Inserted as a starter in center field on July 15, he batted leadoff and hit a single and double. In an August 25 NIL playoff game with Kearney Nebraska, Snyder had two hits, scored two runs, and stole a base. Two days later, Yankees scout Joe McDermott signed the speedy 18-year-old to a contract with the McAlester Oklahoma Rockets of the Class D Sooner State League for 1953. The bonus was $1,000. In the fall of 1952, Snyder attended the University of Nebraska, in Lincoln. He was there for one semester but never re-enrolled. If baseball hadn't worked out, then he'd have returned to Nelson and gotten a job. Snyder toiled in the New York Yankees minor-league system for a half-dozen seasons, while going to spring training with them three or four times. He usually stayed in camp about a month, but never left camp with the big club. When asked if not getting the call to join the Yankees was frustrating, he said no, because he usually got promoted to higher levels each season, and that was progress. Upon arrival in McAlester, Snyder was an instant sensation. His first 50 at-bats produced 31 hits, for a stratospheric .620 batting average. The July 16 edition of the Nelson Gazette headlined his 27-game hitting streak. In late July, the Norman Oklahoma Transcript reported that Snyder 'just isn't being stopped' and still had a robust .461 average. Snyder culminated his freshman campaign with a league-leading .432 mark - 'the highest batting average in all the minors in 1953.' For that distinction, he was awarded the Hillerich & Bradsby Silver Bat, in addition to the A.G. Spalding & Bros. Trophy. His 240 hits and 74 stolen bases both topped the league, and he compiled 310 total bases, 137 runs scored, and 84 RBIs. Fittingly, McAlester won the league championship, and Snyder was tabbed the SSL's All-Star center fielder. Although Snyder hit only two home runs in '53, Rockets skipper Bill Cope said, 'Russ doesn't pull the ball yet the way he should. .. When he really learns to get around more on the pitch, Russ will start dropping them over the fence consistently.' In 1954, Snyder reported 'to Ocala, Fla., for training with the Yankees' Class AA contingent' and continued his scorching .400-plus pace into the exhibition schedule. He earned a starting spot with the Birmingham Alabama Barons of the Class A Southern Association. However, it was reported in April 1954 that Snyder's contractual arrangement with Birmingham expired on May 8. After appearing in just three games, he voluntarily opted to join the Quincy Illinois Gems of the Three-I League Class B. Unfortunately, in mid-May he suffered a serious leg injury. When he returned to Quincy's lineup on June 18, he reinjured the same leg. On Wednesday morning, July 21, cartilage was taken from Snyder's damaged right knee at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City. He hit .324 in 28 contests with the Gems before his second season was shut down prematurely. On September 29, 1954, Russ's father, William, passed away in Superior, Nebraska, at the age of 57, after an extended illness. In the offseason, as part of his rehab, Snyder walked extensively, which included co-management of a trapline with about 100 traps. He reported to the Binghamton New York Triplets of the Class A Eastern League in spring 1955 and joined a roster including future Yankees Johnny Blanchard and Jim Coates, under the managerial eye of former Yankee Snuffy Stirnweiss. 'I believe his knee is healed perfectly,' said Stirnweiss. 'I've watched him closely for two weeks, and he doesn't favor it a bit. He's the Richie Ashburn-type hitter - fast, uses his head and uncanny with drag bunts. .. Russ doesn't hit for power. .. Russ is no Mel Ott .. but he can sure handle that bat.' The Ashburn comparison prompted Charlotte North Carolina Observer sports editor Dick Pierce to ask in a headline, 'Do Yanks Own Second Ashburn?' Snyder batted .261 in 93 games. On Sunday, February 26, 1956, Snyder married Patricia Ann Greenwood in the Methodist church at Nelson. Known to all as Ann, she also was a 1952 graduate of Nelson High School. Snyder returned to Binghamton in 1956 under new skipper Freddie Fitzsimmons. He played in 140 games and batted .286, fueled by 155 hits - 35 for extra bases, including five home runs. The Nebraska native's improved play resulted in a promotion in 1957. Snyder was assigned to the New Orleans Pelicans, under player-manager Peanuts Lowrey, in the Class AA Southern Association. He hit .281 and, despite smacking only one homer, collected 50 RBIs. As an outfielder, he handled 348 chances, making eight errors for a .977 fielding percentage. Snyder rejoined the Pelicans in 1958, piloted first by player-manager Charlie Silvera, who then was replaced on August 19 by player-manager Ray Yochim. He connected for 13 home runs - the only time in 18 professional seasons that his homer total reached double digits - with 67 RBIs, the second-highest total of his career. On June 25, one New Orleans newspaper said 'the promise being shown .. by Jack Reed and Russ Snyder in the outfield assures Casey Stengel and the Yankees' owners of some fine young talent by 1960 - maybe sooner.' Russ Snyder THE TOPPS COMPANY Snyder remained in spring training with the Yankees into early April 1959 before he was sent to the Richmond Virginians of the Triple-A International League. His apprenticeship, so far, consisted of six-plus years in the Yankees' farm system. Before appearing in any games, though, Snyder and Tom Carroll were swapped rather unexpectedly on April 12, to the Kansas City Athletics for Bob Martyn, Mike Baxes and cash. On April 18, 1959, Snyder made his major-league debut at Cleveland Stadium. Pinch-hitting in the fifth inning of the Athletics' 13-4 defeat, he grounded back to Indians pitcher Don Ferrarese. After one more hitless at-bat two weeks later, Kansas City sent Snyder to the Triple-A Pacific Coast League, where he hit a resounding .336 with a .790 OPS in 63 games with the Portland Oregon Beavers. In the outfield he muffed only three of 165 chances for a .982 fielding percentage. After Kansas City outfielder Whitey Herzog got hurt, the Athletics brought Snyder up to KC on July 10. Eager to play, Snyder, 25, quickly adapted to his role as a reserve. In addition to filling in for Herzog, he spelled center fielder Bill Tuttle, left fielder Bob Cerv, and right fielder Roger Maris when they were injured. Snyder anticipated more playing time against right-handed pitching based on Athletics' manager Harry Craft's use of him to that point. 'He hits well .. he will be anywhere from .320 to .345,' Craft predicted. 'He works hard, keeps to the rules, and is always seeking improvement.' When asked what advice he would give Little League and Junior Legion players, Snyder said, 'Keep hustling and work hard. ..You must be willing to sacrifice to get ahead in the game.' In 73 games 55 starts in '59, Snyder hit .313 and fielded .986. He received one first-place vote for American League Rookie of the Year honors, finishing third behind Bob Allison and Jim Perry. Further acclaim came when Snyder 'was named to the J.G. Taylor Spink and Sporting News Rookie All-Star team for 1959.' That off season, Snyder returned to his hometown, to accolades and gratitude. A 'Russ Snyder Day' was held in Nelson on October 5. At the banquet that evening, a group of locals presented a new shotgun to Snyder, a devoted wild-game hunter and avid sportsman in the offseason. Of his future in the major leagues, Yankees scout McDermott said 'Russ ..will certainly get his licks from that burning desire to improve. .. Russ will go far.' When the Athletics dealt Cerv to the Yankees for infielder Andy Carey on May 19, 1960, it appeared that Snyder might crack Kansas City's regular lineup. He wasted no time in contributing that same day by driving in four runs in a 7-4 win over the Baltimore Orioles. In a mid-June interview with Hastings Daily Tribune sportswriter Doyle E. Smith, Snyder said 'I get edgy when I'm on the bench .. but I work hard at all times.' Smith concluded that Snyder is 'one that more major-league teams should have in their organization.' But Snyder started only 64 of his 125 appearances with the A's in '60, and the spotlight that had shined brightly the previous season was dimmed somewhat when his batting average tapered to .260. In December 1960, the Kansas City Athletics were purchased by Charlie Finley, an unconventional owner fixated on change. Finley hired Frank Lane as his general manager in January 1961, only to fire him that August. 'Trader Frank' was a deal-maker extraordinaire, who set about altering the Kansas City roster upon his arrival. He talked to White Sox owner Bill Veeck, who was interested in acquiring Snyder, but Veeck's return offer was hollow. The relentless Lane's first KC transaction came on January 24, a seven-player deal with the Baltimore Orioles. Snyder and Herzog were sent to the Birds for Jim Archer, Bob Boyd, Wayne Causey, Clint Courtney, and Al Pilarcik. Lane was optimistic about Causey. In Baltimore, GM Lee MacPhail sought to deepen his outfield pool with the acquisition of Herzog and Snyder, whom he had known since their days in the Yankees' organization. MacPhail said he had 'a great deal of respect for their ability and desire to play.' Snyder's hometown Nelson Gazette said simply, 'the trade moves Snyder from an 8th place club to a pennant contender.' In '61, Snyder hit a solid .292 in 115 games with the Orioles, stroking 12 more hits in 12 more at-bats than in 1960. As spring training 1962 approached, Maryland sportswriter Dick Kelly recounted Snyder's late-season surge in '61 and touted his speed, which produced 24 infield hits, half of which were bunts. By June 17, Snyder was batting .326 and going deep more frequently - 'attacking the ball, snapping his wrists at impact.' No longer was he 'lunging and sweeping at the ball'—instead, he was keeping his hands calm and trying 'to put everything into the swing at one time.' In addition, he was 'seeing the ball better.' Snyder was hitting more line drives but admitted having difficulty with left-handed pitching; he appreciated being platooned. He switched to a heavier bat and adapted a 'killer instinct' at the plate. New skipper Billy Hitchcock wanted him swinging away, and he was. Snyder finished the '62 season with a team-best .305 batting average, while achieving major-league personal highs in hits 127, homers nine, and total bases 181. The 1963 season resulted in more career highs for Snyder in the majors: games played 148, plate appearances 479, doubles 21, stolen bases 18, and walks 40. In 14 more outfield chances than in '62, he committed three fewer errors. Although Snyder's batting average dropped to .256, the Orioles led the American League as late as June 8 and finished 10 games over .500 in fourth place. J. Suter Kegg of the Cumberland Maryland Evening Times suggested in April 1964 that Snyder's middle initial H stood for 'Hustle.' In Kegg's opinion, 'No .. other big-league player put more into playing baseball than Snyder.' Yet, Kegg lamented, he was a utility outfielder, 'who has to fight for a job every spring.' Kegg called Snyder 'one of the majors' top unsung heroes.' Snyder's approach is that 'he should give it everything he has.' He did. He ran daily wind sprints to build stamina, studied batting practice pitches the same as those during regular season at-bats, and avoided bad habits - he was always prepared. Manager Hank Bauer praised Snyder's approach, saying he's 'the greatest hustler in the game today.' After Baltimore first baseman Norm Siebern was injured, left fielder John 'Boog' Powell shifted to first, and Snyder took over in left. Batting third in the order against the Tigers on May 27, Snyder walked in his first plate appearance, then hit safely in his next two at-bats - the second hit a bunt single that he beat out on a close play. However, he 'jammed his foot on the first-base bag,' which resulted in a fractured fibula 'several inches above his left ankle.' Snyder's leg was placed in a cast, and he was moved onto the disabled list. The Orioles signed Gino Cimoli to replace him on the roster. By July 1 his cast was removed, and he began daily physical therapy in Baltimore. On August 12, the Orioles sold outfielder Willie Kirkland to the Washington Senators and activated Snyder, whom Bauer felt confident was ready to return at full strength. Snyder finished the '64 campaign with a .290 average in 56 games. The Orioles enjoyed their best season since moving to Baltimore, holding a share of first place as late as September 18 before finishing third behind the Yankees and White Sox with a 97-65-1 record. Bauer later cited Snyder's leg injury 'as the blow which prevented Baltimore from winning the 1964 American League pennant.' The 1965 season saw the Orioles again finish third, with a 94-68 record, eight games behind the AL champion Minnesota Twins. Snyder compiled a .270/.323/.322 slash line in 132 games. He averaged .311 at home and .368 against the Cleveland Indians; his lone home run also came against the Tribe. Across all three outfield posts, Snyder was flawless - recording 188 putouts and four assists with a perfect 1.000 fielding percentage. The 1966 Baltimore Orioles featured a quartet of future Hall of Famers Luis Aparicio, Jim Palmer, Brooks Robinson, and Frank Robinson. Snyder wasn't destined for the same, yet nonetheless he proved invaluable in the franchise's first championship. Snyder's tie-breaking, two-run homer off Washington's Dick Bosman on June 8 helped Baltimore sweep a doubleheader and move into first place to stay. From June 19 through July 9, he assembled a 14-game hitting streak, including a 5-for-6 performance on June 26 in Anaheim against the Angels. He had four singles and a triple, scored three runs, and knocked in one. Although he didn't have enough plate appearances to qualify officially, Snyder's .347 average through July 9 was the American League's highest. However, he said, 'Frank Robinson is really leading the league. .. I'm just a utility player.' Robinson, the eventual Triple Crown winner and AL MVP, was batting .314. In early September, sportswriter Doug Brown asked Snyder if lacking the required number of plate appearances was frustrating. Snyder didn't deny that it was but said philosophically, 'maybe they're doing me a favor by platooning me. They might be prolonging my career.' In Kansas City on September 22, playing center, 'Snyder dove for Dick Green's ninth-inning line drive - and speared the Orioles' first American League pennant. .. Snyder's catch completed a 6-1 triumph over the Athletics .. and made Baltimore a major-league title town for the first time since 1896.' Snyder played in 117 games and posted a .306/.368/.413 slash line in 421 plate appearances, one nearly identical to his sparkling '62 season. He equaled his major-league career highs in doubles and triples and established a new personal best with 41 RBIs. The Orioles' four-game sweep of the Los Angeles Dodgers in the 1966 World Series was the crowning glory to an outstanding campaign. In the bottom of the second inning of Game One in Los Angeles, the Dodgers trailed, 4-1, but had men on first and second with no one out. LA catcher John Roseboro hit a sinking line drive to right-center. Snyder sped to the ball, 'dove and speared it to retire Roseboro and choke off a possible big inning.' Baltimore Sun sports editor Kent Baker labeled it a 'turning point' as the Birds won the opener. Needless to say, 1966 was a career year for Russ Snyder. Previously, Snyder had platooned with Paul Blair in center field, but Blair - 10 years Snyder's junior and an eight-time Gold Glover to be - won the job outright in 1967. In 108 games, Snyder's batting average plummeted to .236. That fall, he pinpointed the start of his descent, telling The Sporting News, 'It happened in that 19-inning game in Washington early in June. .. I tore a muscle in my elbow, probably from overswinging. .. My average was up to about .315 at the time, but from that point on, I went down. .. I couldn't grip a bat and I couldn't throw.' The Orioles finished sixth in the American League in 1967. On November 29, Snyder's tenure in Baltimore ended. He, Aparicio, and John Matias were traded to the Chicago White Sox for Don Buford, Bruce Howard, and Roger Nelson. The White Sox, with Eddie Stanky at the helm in 1968, was Snyder's fourth major-league organization. Uncharacteristically, through his first 36 games, he was hitting .123 with no RBIs. But on June 11, against the Yankees in New York, he drove in five, aided by a grand slam - the first of his career - in Chicago's 9-5 win. Three days later, Snyder was traded to the Cleveland Indians for outfielder Leon Wagner. The 'real' Snyder re-emerged in Cleveland. In his first 14 games for the Tribe, he batted .365. Following a 4-1 win over the Twins on July 1, he attributed his improved play in Cleveland to a 'better mental attitude,' feeling 'more at ease,' and 'playing for a manager like Alvin Dark.' The White Sox, he said, had wanted him to pull the ball; Snyder confessed that he 'got all mixed up.' He wasn't mixed up in Cleveland, where he hit .281, drove in 23 runs and scored 30 in 68 contests for the third-place Indians. In the outfield, he handled 111 chances with one error, and he played one errorless game at first base. The 1969 Cleveland Indians were part of the newly formed, six-team AL East division. They finished last at a league-worst 62-99. In 122 games, Snyder hit .248, 11 points above the team average of .237. During spring training in 1970 with the Indians in Tucson, Arizona, Snyder again prepared to compete for an outfield spot as he entered his 12th major-league campaign. However, as camp broke and teams went north, Snyder was traded for the fifth time in his career. The expansion Seattle Pilots had moved to Milwaukee in 1970, after one bad season in Seattle, and became the Milwaukee Brewers. On April 4, Snyder and Max Alvis were shipped to the Brewers for Roy Foster, Frank Coggins, and cash. Snyder and Tito Francona - both 36 - were the oldest players on Milwaukee's roster. Entering a June 12 contest in Cleveland, the Brewers were on a 17-game road losing streak, and Snyder was in a 1-for-24 slump. He hit his second and final major-league grand slam that night to lead Milwaukee to a 4-1 victory. Overall, he saw action in 124 games for the fourth-place club and hit a career low .232. In late February 1971, Snyder reported to spring training with the Brewers in Tempe, Arizona. He homered in a 7-4 exhibition win over the Tokyo Lotte Orions on March 18. Nonetheless, the Brewers released him on March 27, 1971, ending his baseball playing career after 18 professional seasons. In the majors, he produced a .271/.325/.363 slash line over 1,365 games. He collected 984 base-hits - 221 for extra bases - with 42 homers, 1,318 total bases, and a .688 OPS. In the outfield he had 1,942 chances, 1,856 putouts, and 49 assists, as he committed 37 errors, recorded 13 double-plays, and fielded .981. Prior to his release by the Brewers, Snyder had 'bought a bar, and built a steakhouse beside it' in Nelson. Snyder had appeared before the Nelson City Council and said 'if you will approve liquor by the drink, then I will build a steakhouse'—they did. The establishment was owned and operated by Russ and his wife and was called Russ and Ann's Sportsman's Corner. 'He painted an infield on the dance floor, baselines included, and filled the place with his baseball treasures. Twelve years later the building was struck by lightning and burned to the ground.' Snyder also worked 'as a soil conservation technician, constructing terraces and dams for erosion-plagued farms' in south-central Nebraska for 18 years. He considered a return to big-league baseball as a hitting coach in the late 1970s after receiving a verbal commitment from former O's third base coach Billy Hunter. However, Hunter's managerial circumstances with the Texas Rangers later changed, thus nullifying the potential role for Snyder. Also, the infamous major-league baseball strike in '94 and the negotiations that followed took a toll on his benefits package, resulting in the loss of his health insurance at the time. He had to independently find another carrier. Presumably, players who had played through 1970 were to retain such benefits—1970 was his final big-league season. Snyder repeatedly called the Commissioner's Office for an explanation but didn't receive one to his satisfaction. On June 12, 1995, Russ's mother, Ruth, 85, passed away in Kearney, Nebraska. Snyder is listed with a biography and pictorially presented in an attractive display in the Museum of Nebraska Major League Baseball, in St. Paul, Nebraska. He served as the museum's Grand Marshal for its annual Grover Cleveland Alexander Day parade in July one summer. There is a Russ Snyder baseball museum located in his birthplace of Oak, but it is currently closed. In 1992 Snyder was inducted into the Nebraska Baseball Hall of Fame in Beatrice. He is also a member of the Nebraska High School Hall of Fame, inducted in 2008. His inscription, in part, reads that he would return to Nelson 'to coach junior high basketball and referee high school basketball.' Also, following retirement, he coached 'baseball and girls' basketball in Lawrence/Nelson.' In a 2013 interview with Mike Klingaman of the Baltimore Sun, Snyder spoke fondly of his years with the Orioles: 'We were one happy family. .. Our kids all played together. Our wives were friends. We spent our off days together. Nobody was left out. .. That's why we won as much as we did.' In 2016, Snyder attended the 50-year reunion of the 1966 Baltimore Orioles championship team. Looking back in 2022, Snyder named Camilo Pascual as the toughest right-handed pitcher he faced because the Cuban had a good curveball. He thinks Orioles second baseman Davey Johnson was underrated. He has great respect for Whitey Herzog, Boog Powell, and Brooks Robinson, among others; he speaks highly of all his Orioles teammates. He roomed with Luis Aparicio when they were on the road. When asked what he was most proud of in his big-league career, he said, 'I knew I could play baseball well, I wanted to show others I could, and I did. Not every player is willing to be a reserve—most want to start and don't like it when they don't. I was a utility player.' Snyder always was prepared to play as a reserve or a starter, and that contributed heavily to his big-league success. Ann, Russ's wife, succumbed to cancer in 2002. They were married 47 years. The Snyders had three children, Pam, Sharon, and Scott; seven grandchildren; and eight great-grandchildren. He said he had a small stroke in 2012, got a pacemaker, and was doing fine. As of May 2022, Snyder, 87, continued to reside in Nelson. Last revised: May 11, 2022 Article Source |